Maybe don't regulate study pills like opioids

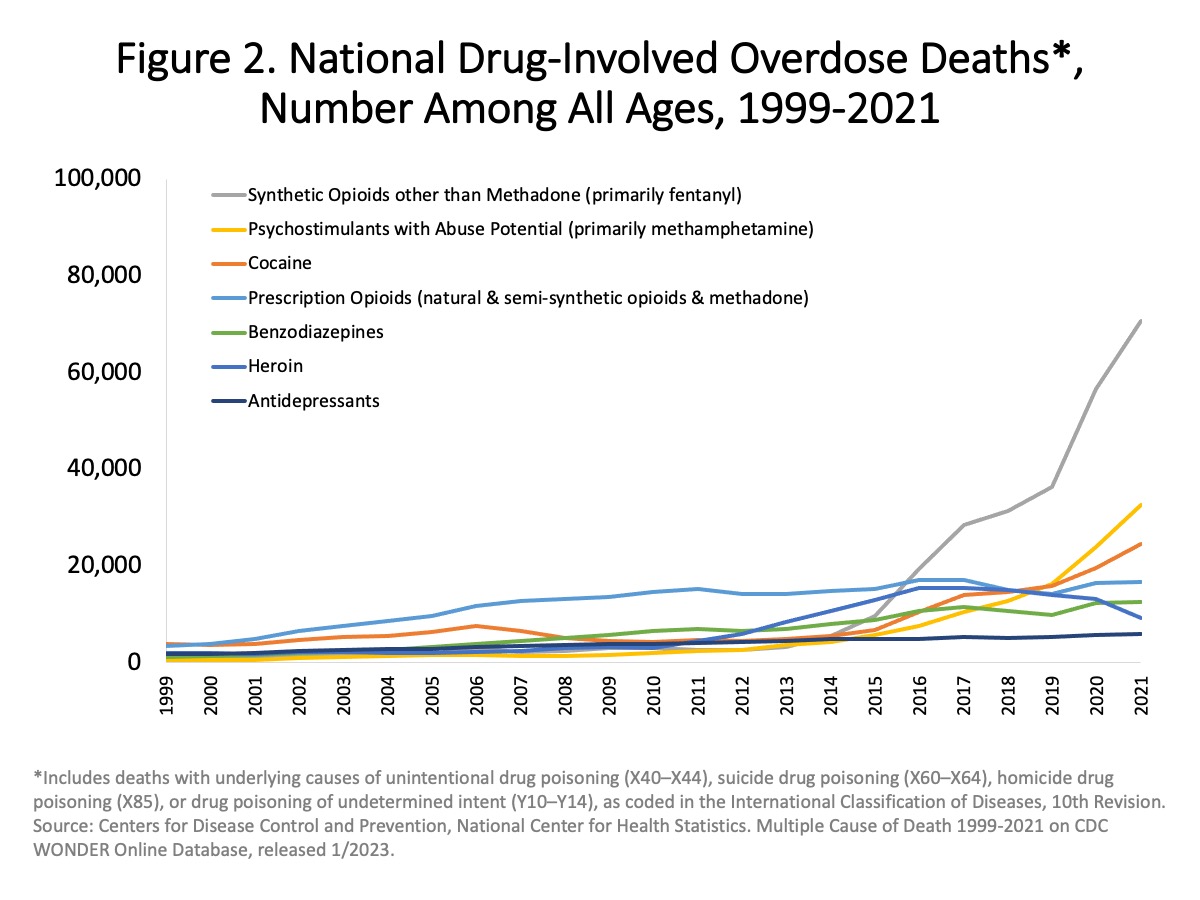

One of these kills 70 thousand people per year in the US; the other about eleven per quarter. But they’re both Schedule II controlled substances.

Being a Schedule II amplifies supply shortages, wastes compliance attention in the supply chain, and provides a veil of secrecy for manufacturers to manipulate prices. If this is justified by risk, fine, but if not, bump it down a notch.

Scheduled drugs were born in 1970 when Nixon, author of the war on drugs, passed the Controlled Substances Act. Originally, amphetamine was in the less-severe schedule III. Let’s just put it back.

Be safe: This article is about regulations + market dynamics. It’s not medical advice for you. Amphetamine affects your heart and mood, and can trigger psychosis or manic episodes. It appears safe in part because it’s used under medical supervision and with risk screening. Get yours through a doctor.

- Quotas cause shortages

- Was amphetamine harmful in the 60s?

- Is it harmful today?

- Telehealth and Cerebral

- Distributors and red flags

- Better buckets

- Appendix: overdose charts

- Notes

Quotas cause shortages

There are periodic shortages of prescription amphetamine. Given how the market is structured, this feels inevitable:

- Because it’s a schedule II, users are not allowed to accumulate a buffer stock

- Production quotas limit the total amount of drugs that can be produced per year, and they’re pre-allocated; a production issue at one company doesn’t release that quota to someone else1

- Brand vs generic versions further segment the market

Teva had an issue at their factory last year which they blamed on pandemic labor shocks. It caused multi-month across-the-board shortages of adderall, but the branded version resolved its supply shock months earlier. Beyond the sleaze factor here, healthy markets are good at price setting and reacting to demand; this isn’t a healthy market.

When generic Adderall XR was new, Shire bribed insurers to not cover it. Even when the co-pay for the brand was higher than retail for the generic, health systems ended up prescribing the more expensive one. Buyers can switch if they know, but inventory, price and product quality are for different reasons all secret, and pharmacists can report you to a PDMP if they catch you shopping. ‘Shopping is illegal’ = market failure.

Was amphetamine harmful in the 60s?

I started my reading thinking ‘this drug is mostly harmless’ and still think that, but with an asterisk: people in the 60s used very high doses of things. There are some horror stories:

Russell Monroe and Hyman Drell, stationed at a military prison in 1945, encountered large numbers of agitated, hallucinating patients. A survey revealed that one quarter of the imprisoned personnel were eating the contents of Benzedrine Inhalers, which then contained 250 mg of amphetamine base.2

See Benzedrine Alert in a late 40s Air Surgeon’s Bulletin for a lighter take.

In 1971 methamphetamine and amphetamine were moved up from schedule III to schedule II. This change is for amphetamine and meth, which makes me think they actually wanted to regulate meth, and just didn’t know the difference. The federal register cites a ‘Report of the NYC Special Committee on Amphetamine Abuse’, which I couldn’t find, but I did read a 1970 NYT article on pep pills.

ADHD wasn’t a concept yet:

The drug is also recognized as an aid to children who are excessively active because of minor brain damage; for some reason not clearly understood, the stimulant seems to calm them.

In 1970, the DSM had just changed to ‘hyperkinetic reaction of childhood’, from ‘minimal brain dysfunction’. The ADD designation came later, in 1980, and ADHD (renamed in the late 80s) only took shape as a syndrome with known behavioral, neurological and genetic correlates in the 90s3.

Also, the NYT’s bad take 8-ball turned up the worst argument about production and diversion: ‘hopefully reducing legal supply will reduce illegal demand’.

The Justice Department has also found and closed down literally dozens of clandestine amphetamine production plants in this country that supplied directly to the illicit market. The F.D.A. can exercise little or no control over abuses of this sort, but it hopes the illicit traffic can be curtailed by diminishing the present excessive legitimate production.

Regulation caused prescriptions to drop, and in 1972 the production quota for amphetamine was lowered 1/20 of estimated 1969 production. But everyone switched to coke2. A very 90s RAND whitepaper has survey data showing cocaine prevalence increasing through the 70s and decreasing after the mid 80s, with the peak around 10% in 1979 for 18-25 year olds. (But cocaine ODs spiked in 85 and peaked in 89).

Is it harmful today?

Compared to the 60s:

- 1-2% of adults have prescriptions, then and now

- I think far more teenagers have prescriptions today

- The use of diverted pills for test-taking, rather than recreation, may be more prevalent

- Prescriptions today are more likely to be for ADHD, whereas in the 60s and earlier they were used as anti-depressants. Prozac only came on the market in the mid 80s.

- XR formulations are new and manufacturers say they reduce high-dose recreational use

I pulled the adverse event reporting system for Q4 2022, and found4:

- 103 deaths involving amphetamine

- 54 of those involved an opioid

- 21 had no opioids but did have methamphetamine or cocaine

- and 28 others, of which 11 were amphetamine-only

You’ll see headline numbers like five million adults misusing stimulants. They aren’t. This comes from the NSDUH, a national survey which defines misuse as ‘any way a doctor did not direct you to use it’. This isn’t measuring harm, it’s measuring whether you have a doctor.

Compton et al distinguished between ‘misuse’ and ‘use disorder’ and made the number way smaller. They claim 16 million users, 5m misusers, and 400k with use disorder. The motivations for misuse were 55% ‘be alert or concentrate’, 22% academic.

I pulled some random pubmed articles but they’re not compelling. This one about misuse and adverse effects complains a lot about use for academics without explaining why that’s harmful:

prescription stimulants are most commonly misused to enhance school performance …

According to a Web survey of 115 ADHD-diagnosed college students, enhancing the ability to study outside of class was the primary motive for misuse …

A web-based survey administered to medical and health profession students found that the most common reason for nonprescription stimulant use was to focus and concentrate during studying

I think the argument for why this is bad is kind of split-brained. You end up saying:

- stimulants only improve performance if you have ADHD

- ‘students without ADHD misuse stimulants to improve performance’ (from same article)

Prescribed amphetamine is probably not a gateway drug:

people of any age receiving a stimulant for ADHD have no greater risk for illicit substance abuse compared with the general population

‘Melt your brain’ claims about these meds are from long-term, high-dose meth users, and from rats. The rats get ‘neurotoxicity’ (damage? loss of function?) in some dopaminergic reward circuit. But about that:

One study in rodents reported that 15 daily “binges” with 4 mg/kg amphetamine significantly compromised striatal dopamine integrity5

If my math is right, that’s 60mg / kg / day, which would mean 4800mg for an 80kg average american adult. (I think the average daily adult dose is in the 20-30mg range and the recommended daily maximum is 60mg).

To me this reads like ‘scientists are concerned about brain damage from bricks after they dropped one brick on a rat and it died’.

Telehealth and Cerebral

When the Ryan Haight Act was suspended during lockdown, a new breed of telehealth shops joined the fray who were able to prescribe stimulants without an in-person visit. Cerebral is the most famous and troubled of them.

Health analytics SEO posts are trying to blame telehealth for a 2-year, 20% increase in amphetamine scripts in adults 20-44 (figure 2 in the link). I don’t totally buy this:

- The trend existed pre-2020

- I think nobody knows how many of the new scripts are from telehealth platforms

- Normal psychiatrists also moved online after lockdown, in theory increasing capacity

Also note the even shadier vendors who will sell you adderall without a script at all.

Either way, Cerebral is in various temperatures of hot water. A patient’s family is blaming them for practices that led to a suicide. (One Cerebral doctor denied him a script, and he made a second account and got one).

The DEA is trying to restore Ryan Haight. In theory this breaks Cerebral’s business model, but they already stopped prescribing controlled substances last May because of multiple federal investigations and getting dropped by all the pharmacies.

A Frances Haugen-inspired ex-PM whistleblower is suing them, either for unsafe prescribing practices, if you believe the medical press, or for having his stock taken away, per bloomberg law and the SF superior court.

The point here is that if you’re going to build a telehealth platform, psychiatric or otherwise, diagnosis standards and patient monitoring should be the first thing on your list, not the last.

Distributors and red flags

A less sexy, but much larger, legal story is the multi-state opioid settlement against the top 3 pharma distributors.

Reuters + most news glosses over the distributors’ violations as ‘lax controls’ because every resource that does explain it is long-winded and confusing. An FDA warning letter says Rite Aids in Michigan got multiple shipments where ‘the seal was broken and 100 tablets of Oxycodone 30mg were missing. Fifteen tablets of generic Aleve manufactured by Amneal Pharmaceuticals were inside the bottle’.

How is this relevant to amphetamine regulation:

Suddenly the distributors are trying to comply, but the rules are byzantine. In one example, they’re stopping all controlled substance shipments to indie pharmacies who match ‘red flag’ patterns in dispensing history.

Health and compliance lawyers are critical of the red flags system:

A patchwork of agency enforcement orders. The unclear standards have made some pharmacies reluctant to fill prescriptions6

DEA is … [imposing] bright line standards related to “red flags” and the need for documentation, which are not currently defined in the statute or regulations.7

Enforcement actions based solely on red flags and not actual diversion.8

I have no opinion other than this: if Schedule II is being used to apply onerous compliance rules for opioids, it’s the wrong bucket for study pills.

Better buckets

At some point, our alphafold homelabs will make this discussion obsolete by brewing random amphetamine analogs from nail polish remover and wood alcohol. Until then, it would be good to have better rules.

I’m not saying don’t regulate prescription amphetamine. I 20% believe this stuff is safer than alcohol and tobacco. I 80% believe you want to continue to monitor for bad reactions, limit individual supply to prevent diversion, and screen buyers for risk factors.

But the screen should be cheaper and easier to get than the current diagnostic process, which begins with calling every psychiatrist in 5 zip codes, and if you’re lucky you repeat that process to find a pharmacy that will fill your prescription and takes your insurance.

Stop using quotas in ways that amplify supply shocks.

Lower the bar for 18+ to get a ‘finish 1 essay’ dose. Legalizing this use case removes an incentive for diversion. Stop classifying academics as an abuse case; it’s absurd and it makes all the scholarship and regulation sound phony. Normalizing what is already normal lets you 1) monitor for safety and 2) refocus enforcement resources on actual harm.

Ideally, create stats observatories for every drug with harm potential, and impose supply constraints based on real-world observations, rather than a regulatory cycle.

My actual point: amphetamine, used with medical supervision, isn’t fentanyl, cocaine, or meth. Everyone’s life gets easier if we move it back down to Schedule III.

Appendix: overdose charts

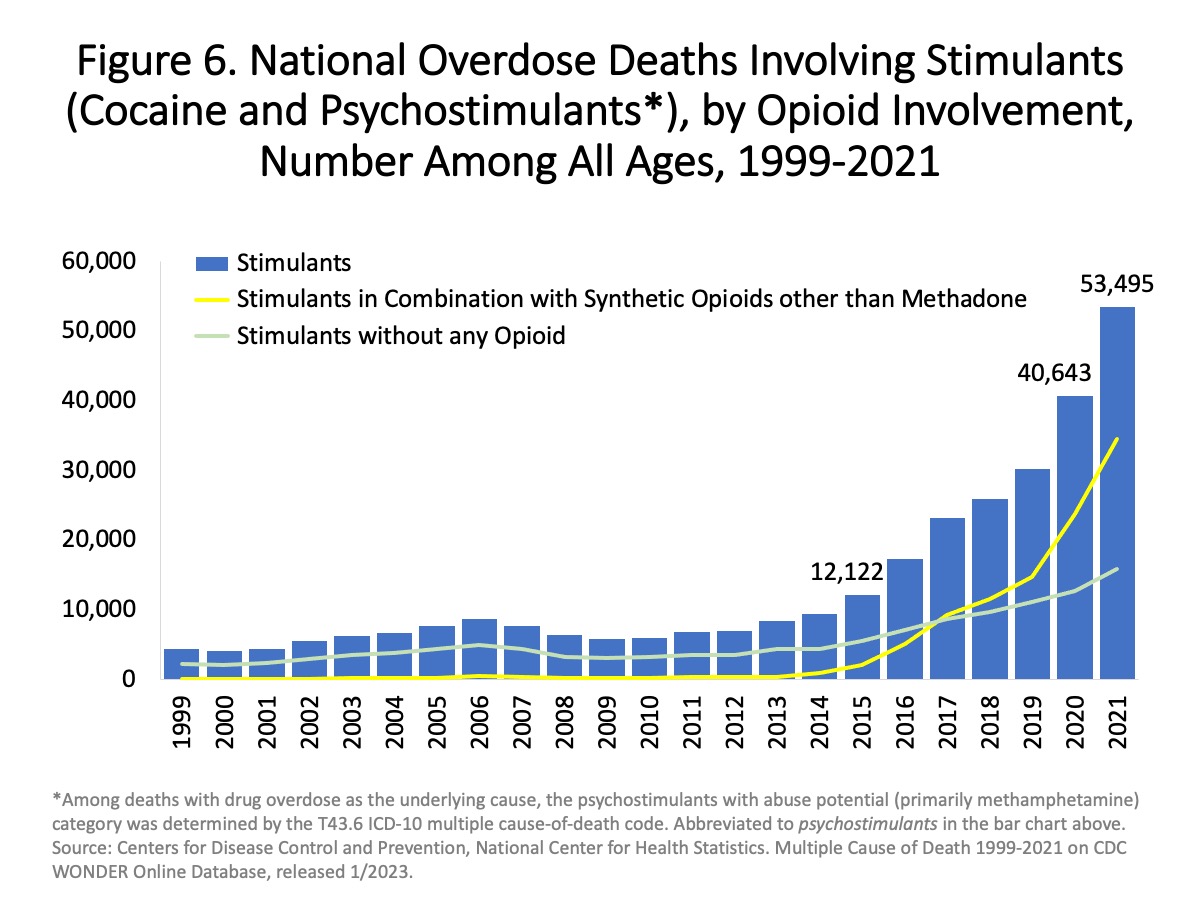

Two charts (from NIH / NIDA).

If you see a chart like these and it doesn’t break out prescription stimulants, don’t let someone tell you the chart is saying anything about prescription stimulants.

You may hear about a growing pattern in OD deaths where the person took both stimulants + opioids. This one blames stimulants for what is probably a fentanyl overdose. Responsible reporting, for example Townsend 2022, will say ‘just give cocaine users test strips’.

Notes

-

21 USC 826(e) and (h) allow for quota increases, but I think only if an individual manufacturer declares a shortage of an input. Not, for example, if Teva has staffing issues and a rival wants to shark their quota.

Also Teva won’t declare a shortage; they have excess supply of the branded version.

Also the justice dept has to agree there is a shortage, and for now they do not. ↩

-

America’s First Amphetamine Epidemic 1929–1971, Rasmussen 2008 ↩ ↩2

-

Though Charles Bradley was giving benzedrine to ‘behavior problem children’ in the 30s. He published in the ‘American Journal of Insanity’ (since renamed). ↩

-

The python notebook for this is checked in here ↩

-

Potential Adverse Effects of Amphetamine Treatment on Brain and Behavior: A Review Berman et al 2009 ↩

-

FDA law blog (this one also lists a bunch of red flag examples) ↩